Sometimes it takes the most oppressive of settings for the purest form of emotional poignancy to arise, and that's what happens in Drake Doremus' deceptive sci-fi film Equals (starring Kristen Stewart and Nicholas Hoult), in which two coworkers in a dystopian, feelingless world end up falling for each other and learn to love when loving is the most dangerous thing you can do. I say "deceptive" because Equals' sterile, futuristic setting and feelings-are-forbidden premise are familiar to other sci-fi movies, notably Michael Bay's The Island (aesthetically) and Jean-Luc Godard's Alphaville (thematically). Though ask Doremus and he'll cite François Truffaut's Fahrenheit 451 as his greatest inspiration. But he's also decidedly not a sci-fi director. At the Tribeca premiere of his new film, Doremus prefaced the screening with, "I'm not an intellectual filmmaker, I'm an emotional one," and asked that the audience "open your hearts."

Somecritics may have been too caught up in the science fiction element of Equals; Alonso Duralde at The Wrap compared it to "THX-1138, The Giver, perfume ads and the Apple Store." What he and others are missing, though, is that Equals is a simple boy-meets-girl story; the restrictive setting mainly proves how much two people are willing to risk in order to be with each other. In fact, the film is altogether anti-technology, despite how it looks on the surface. "I think [the setting] is a device to tell a very human story and examine where society leads us and how disconnected we are with technology," Drake Doremus tells me.

"I think there’s something tragic about where we are headed," he says "It’s scary to think at a certain point, a machine is going to tell us who we should and shouldn’t be with. It’s like, whoa, that’s a little scary." Of course, he brings up Tinder as an example, the obelisk of modern dating. "It’s out of hand!" he says. "In 10 years from now, Tinder could literally be a machine that you put your finger on and all of a sudden it’s like, 'That person!' The magnetic force of the universe doesn’t have a chance to guide you in the direction you need to be in." It's in this anti-technology agenda that he makes clear Equals isn't so much a sci-fi movie as it is a feelings movie. Because only the "magnetic force of the universe" could explain how Silas and Nia were brought together. Figuring out the logistics of how this fictional society came to be—a society where emotions don't exist and people who catch feelings are treated or, if beyond treatable, committed in an asylum—isn't the point of the movie. Hoult and Stewart give exceptional performances as Silas and Nia, and it's the authenticity of their performances that makes Equals, as Doremus put it, an emotional film rather than an intellectual one. He adds, "The movie is really about knowing you are supposed to be with somebody, but resisting it and eventually giving in and seeing how amazing that feels."

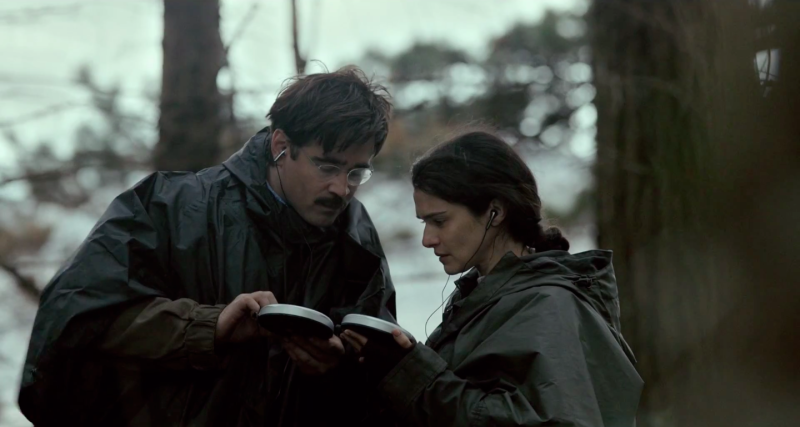

Forbidden love has been a subject of interest in countless films, from Romeo & Juliet to last year's Carol, and even Stewart's own Twilight saga, because they tend to dramatize real-life concerns of relationships—either where you, personally, are at in your life or where we, as a society, are. The same can be said for the absurdist romantic dramedy The Lobster—which came out just two weeks ago—which finds its protagonists (played by Colin Farrell and Rachel Weisz) in a community where romantic gestures are not only forbidden but gruesomely punished. This community serves as an escape from the larger, government-sanctioned society where being single is banned (and punishable by being turned into animals), but both worlds prove to be antithetically oppressive. In the Loners group, the two lovers resort to secret sign language to communicate the unspeakable. I love you more than anything in the world.

The Lobster's unease in regards to dating feel universal. "The anxiety and the pressure that you're under because of how society views people who are single was a starting point for us," director Yorgos Lanthimos tells me. "And considering them failed in life if they're not in a relationship." The way people force mutual likenesses upon each other just so they end up having partners is akin to the way people rely on online dating to find a mate. "Seeing a mutual Facebook like on an app or overhearing someone mention Drake at a bar piques interest, perhaps even tricking you into thinking about a future with someone that doesn't exist," Complex editor Kerensa Cadenas wrote about The Lobster. Lanthimos didn't want his film to be too technology-leaning, though. He adds, "I think doing something that was so topical, focused on a very specific kind of communication and technology would limit the resonance of the film."

Though there's a universal resonance in Equals too, there's also something unmistakably modern about it, or rather it feels like commentary on the modern methods we use to forge relationships. "In a time where we can feel so disconnected and the falling in love process in 2016 is a very disconnected, impersonal process...it can be very inorganic in a sense," Doremus says. "It’s really interesting to examine that, and such an extreme version of that, like in the world of Equals. [Love] still always finds away, no matter how much you fight it. I think there’s something really current about that and about relationships and about finding your one person or soulmate." In the most inorganic of settings, feelings develop organically between the characters of Equals. The subtle ways in which Silas and Nia communicate with each other—a glance held a second too long, excuses for interaction—are basic procedures of flirting, except with so much more at stake. Doremus guides with his cinematic eye, using extreme closeups to linger on his characters' microexpressions. It's in these intimate examinations their expressions of love come alive. There's nothing forced about it; it's the kind of love where its participants can't help themselves. And the film, if you let it, will devastatingly hit you over the head with feels.

Alphaville, Godard's sci-fi/noir film comes to mind, because in that society, called Alphaville, emotions—and even the word "love"—are forbidden. The film's secret agent, Lemmy Caution (Eddie Constantine) ends up falling in love with a young woman named Natacha von Braun (Anna Karina), whose father, the mysterious Professor von Braun, has created this dystopian world. Godard, too, uses close-ups of faces as an unsubtle way of displaying the subtle expressions that come from feelings. Natacha finds herself stunted by her vocabulary—or rather, lack of it—when trying to find the L-word. But she hints at an innate knowledge of it, deep in her conscience ("conscience," by the way, is another word outlawed in Alphaville).

What Equals and Alphaville prove is that despite stripping away the core of humanity (emotions), it's inevitable that these things will still surface. In these films, organic romance sprouts from oppression, countering the sort of forced romance we often put on ourselves today, because technology has allowed for it. Meeting someone through a computer or phone screen eliminates the delicate dance of interest. "Just looking at the Tinder age and where we are... What I'm trying to say is how inorganic things are," Doremus reiterates.

Of course, that isn't to say a Tinder connection can't lead to the kind of real love found between Silas and Nia. But with these apps, there's a tendency to saturate romantic cues, and to forget about the kind of spark that isn't forced. Good news is, Equals also speaks on the longer-term, post-butterflies kind of love. It's also about how romantic human relationships are maintained—that specific, fraught challenge. "It’s not always going to be the first three months, or six months, this honeymoon phase," he says. "I'm sort of examining the idea of how over the course of time relationships change and develop. You have to remember and continue to work on feeling and understanding why you are with that person. I'm thinking about relationships in a longer term kind of thing instead of examining a moment in a relationship or a moment in two people’s lives. This is more about looking at the long term effects of committing to somebody and being with somebody."