Today is Bruce Lee's birthday. The "Little Dragon" was born on November 27, 1940 in San Francisco, CA. And as we recognize and celebrate his legacy, we also mourn the life he never got to live. Bruce died when he was 32 years old, on the cusp of mainstream success in America.

He lives on through his writings and films, and also through the martial arts instructors who follow in his footsteps; my son trains under a 2nd generation Jeet Kune Do instructor. Bruce was a man who valued practicality over form—he disliked the traditional arts’ reliance on stances, believing that these things were too stiff, and thus, predictable. Instead, Bruce believed in Jeet Kune Do—the “Way of the Intercepting Fist.” It was a philosophy that encouraged formlessness—what was flexible and applicable in a "real-life" situation.

Imitators and heirs to the throne have come and gone, but no one has captured the public’s love, loyalty, or imagination in quite the same way. Every new martial arts actor, from Jackie Chan to Jet Li to Tony Jaa, is referred to as "the next Bruce Lee." Even in our quest to escape him, we still return to him, as the unreachable standard by which all others must be measured.

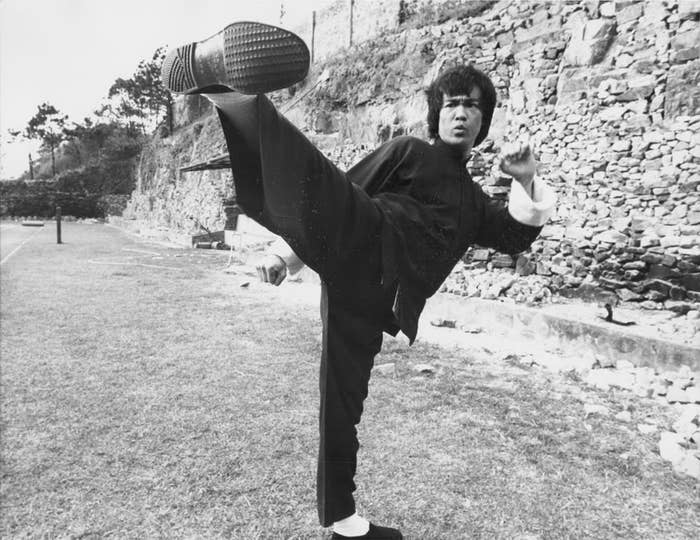

There are a few reasons why Bruce Lee has endured, and they combine to create the legend we know today. There is, of course, his legendary athleticism and fitness. We’ve all heard those hyperbolic "Chuck Norris jokes," but Bruce Lee, scarily enough, was the real deal. From his two-finger pushups to his 1-inch punches, his physical abilities belied his actual size. He was only 5’7" and 135 lbs.—even physically, he was a model of economy and efficiency.

And of course, there was the pure lethality of his persona. Compare Bruce to his fellow action compatriots—most Hollywood fights are intricate, choreographed ordeals, with hundreds of punches, kicks, and counterattacks. Fights can last for twenty minutes or more, and the outcome can shift several times over their course. Bruce, on the other hand, extended his philosophy of efficiency to the fight scenes themselves. There were no wasted movements—every action was consequential. Take, for example, the O’Hara fight in Enter The Dragon. Bruce Lee decimated his opponent with 12 painful-looking, brutal moves. This was not a man to be playfully sparred with—this was a man to be feared.

As an Asian-American kid growing up in the suburbs, I was drawn to Bruce Lee. To many of us Asian boys, Bruce was more than a good fighter. He was a symbol of masculinity—he was an ethnically Asian male role model in a Western society where so few existed, before or since.

The Asian-American male undergoes a systemic humiliation in America, and it’s not always explicit. After all, the positive stereotype of the Asian male is that of an intelligent, bookish math nerd. Being considered smart is better than being considered stupid. There are, however, negative implications to this.

Acceptance of positive stereotypes is an implicit acceptance of negative stereotypes—although we Asian men are considered book smart, we are also said to lack passion, emotion, and raw sexuality. Our penises are rumored to be small, our social interactions are perceived as awkward, and any sexual interactions we do have must be bizarre or creepy. In the same way that black men are hyper-masculinized (and thus, are perceived as violent and threatening), Asian men are hyper-feminized (and thus, are perceived as no threat at all).

Is there a basis of truth to these stereotypes? My parents raised me to believe in the value of hard work above all else, including my social life, and that the key to success in this country was to study hard and get the best grades possible. I later learned (thankfully, in time) that hard work alone would make one an assistant to the leader, but never the leader himself. Success in America meant networking, socializing, and knowing the right people, in addition to working hard. It also meant assertiveness—that at some point, you had to fight back, protest, and disagree with those around you to earn respect. Our parents did the best with what they knew, but the result—a generation of young, Asian-Americans which, by and large, is politically disengaged and much too passive—is unfortunate.

Bruce Lee stood in direct contrast to the "deficiencies" that America saddles upon Asian men. Physically, Bruce was classically handsome, and he exuded virile sexuality. He was all greased muscle and sinew—a coiled panther, ready to pounce. Bruce had several romantic scenes in his films, and that, by itself, was incredible to see. Bruce was a ‘desirable’ Asian man, and in a society where Asian men are considered eunuchs, this was a welcome change of pace.

Bruce was also an ‘angry’ Asian man. Although he came from an ethnic heritage that valued unity and the importance of immersion, Bruce knew how to scream, and holler, and challenge those who did him wrong. He was ‘Asian-American,’ in the truest, hybrid sense of the phrase. The film The Chinese Connection stirs the blood of any Asian man who watches it. Here, we see a liberated Chinese man who doesn’t take insults from anyone—a man who is real, and emotional, and uncompromising in his righteous anger. It was this unhinged emotion, this ability to cry manly tears, that thrilled us so. Not everything had to be calculated and measured, and inscrutable—not everything had to be intelligent.

Sometimes, you just want to get mad and scream. I think of Bruce in my worst moments—when I am discriminated against, when I am underestimated when I am wronged. I think of Bruce when I speak up for myself against my better interests—when standing out is more important than blending in. I think of Bruce when my sense of justice trumps my passivity. Bruce is the ‘id’ that whispers in my ear—that bigots treat me with disrespect because they think they can. They think I’ll be passive, but I have a voice. I can use it to affect change. I can scream.

In his eulogy to Malcolm X, Ossie Davis referred to Malcolm as “our own black shining prince.” For Asian men, Bruce fulfills the same role—our own Asian shining prince, who told us to be vocal, proud, and outspoken for who we were, and for everything we could be.