For six years, four months, and five days, Reminisce Smith sat in the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for Women, a 45-minute drive north from the Bronx, where she was born. Separated from her son, Jayson, and husband, Papoose, she plotted her comeback, studying the rap game. Soon, she came to a conclusion: With the exception of 2Pac, every rapper who served time suffered for it, career-wise, upon release; none found greater success. With social media now allowing artists to release music and address fans directly, the MC we know as Remy Ma knew she had to start rapping the moment she touched ground.

And so she hit the studio hours after being released from prison on August 1, 2014, meeting DJ Khaled to record the “They Don’t Love You No More” remix. One week later she knocked out a song with Jadakiss. Then a record with Ty Dolla Sign. Then, since it was summer 2014, she touched Bobby Shmurda’s “Hot Nigga” instrumental. She was 34 years old, without state ID or driver’s license, without health insurance. She had to find a school for her then 14-year-old son, who was living out of state at the time. But she had a plan, and she stuck to it: She’d reestablish her music-industry presence before getting her life in order.

“Looking back,” Remy, now 37, says, “I guess it was a good decision.”

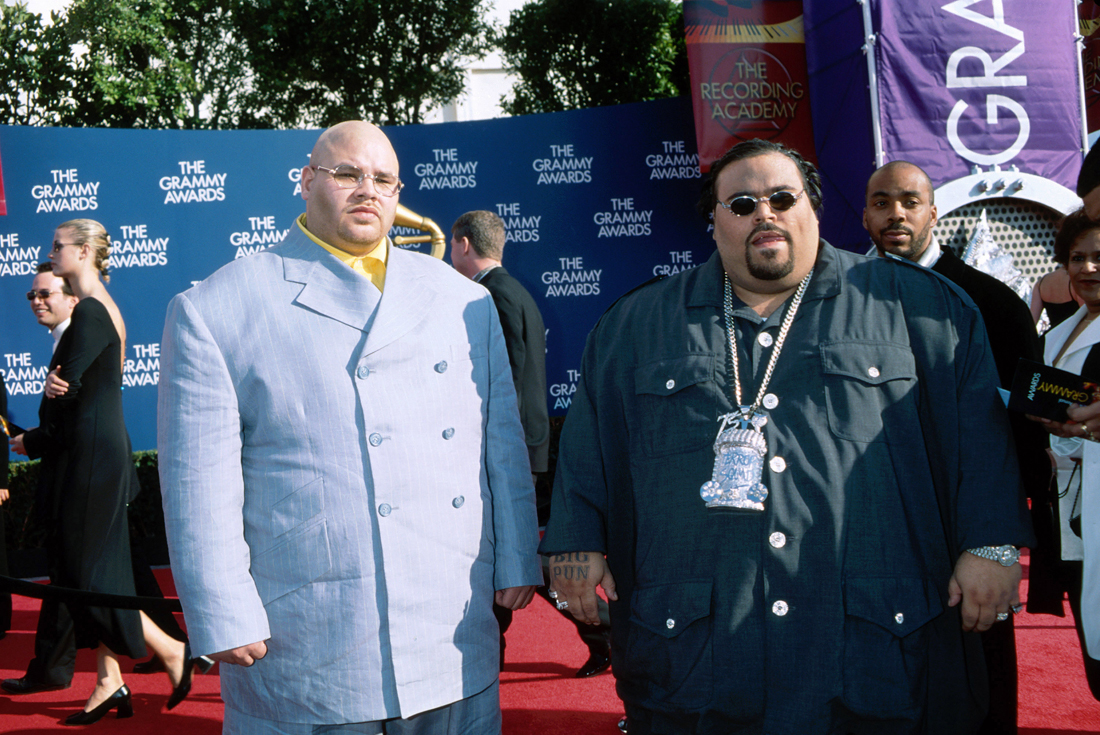

There was more to come. In 2015, Remy joined the cast of VH1’s reality series, Love & Hip Hop: New York, establishing a footprint in another medium. She also scored a hit record with “All the Way Up,” a collaboration with Fat Joe and French Montana that went double-platinum and spawned a slew of unofficial remixes.

But as Remy’s plan unfolded, a clash brewed with Nicki Minaj, the Queens MC who had ascended to rap’s A-list during Remy’s incarceration. Like most rap battles, it escalated from subliminal disses to calling out names. In February of this year, a few weeks following the release of Plata o Plomo, her album with Fat Joe, Remy unleashed “Shether.” A savage seven-minute assault on her rival that left few stones in Nicki’s past unturned, “Shether” peaked at No. 2 on the iTunes rap chart. Remy then went on a press run that, in a way, doubled as a victory tour.

The comeback was complete. But she learned something during the process that left her with a bittersweet feeling.

“It’s a popularity contest,” she tells Complex over the phone in early spring. “I don’t really care about rap the way I used to because there is so much politics. I just do what I do. I write, I talk my shit, say what I want to say, bounce around on the beat, and I keep it moving.”

She added that she feels constrained with the direction of her music. She’d like to diversify and address different topics. But she can’t, she says, because the public prefers her rapping about certain things in a certain way over a certain type of production. “I actually have some dope records that are actually about something,” she says. “I just never get them close to the forefront because it’s not what people be wanting to hear.”

There’s something sad and wrong when an artist like Remy Ma, someone who has survived so much to reach the point she’s at now, feels boxed-in and unable to express herself in her totality. Throughout her career, she’s been so stubborn, so sure of what she wants and what’s best for her. What’s stopping her now?

The answer, of course, is money. “If I didn’t have bills to pay then I could do any record that I want,” Remy says. “I do what I do because it’s fun and I love my craft, but this is a business and this is my job. You can go into your job and do the job that’s expected of you or you can do the job that you want to do. It’s going to affect your paycheck.”

"I don’t really care about rap the way I used to because there is so much politics."—Remy Ma

Remy Ma always had something to say. An honor roll student, she wrote poetry about growing up in the Castle Hill section of the South Bronx. She had a tough upbringing—her mother was locked up for a time, her biological father didn’t appear until she was 18. Those experiences led her weighty subjects once she started rapping in junior high. The first song Remy ever recorded was titled “Suicide,” written when she was 13 years old. “Do you think about dying?” she asked on the record. “Why would you take your own life?”

“If I were to write that now it would be considered deep,” Remy says in her husky voice. “I never had the bubblegum kiddie-bop rhymes.”

Which is why one of her favorite records on Plato o Plomo is “Dreamin,’” a pensive account of her journey from “Castle to Beverly to Bedford Hills.” It wasn’t considered for a single, she says: “It wasn’t radio friendly. It wasn’t…whatever. There was a time when DMX was winning with records like, ‘I’m slipping, I’m falling, I can’t get up.’”

DMX was the biggest rap star in the world in the fall of 1998 when he released the meditative “Slippin’,” from his second album, Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood. The lyrics are a raw recollection of drug abuse, group homes, crime and reckless, self-destructive behavior. He didn’t bend to the forces of the marketplace; he shaped the marketplace.

It was around this time when Remy scored her big break. As the legend goes, one day when she was 17 years old, she bumped into one of Big Pun’s friends outside of a Bronx grocery store. Knowing that she was an aspiring rapper, he invited her to Pun’s place nearby.

Luxury cars and dirt bikes were parked outside the house as three Shar Pei’s roamed the front yard. Inside, at least 25 people had gathered, and sitting at the center of it all was the 500+ pound platinum rapper Big Pun, on a mattress propped up off the floor, wearing nothing but a pair of boxer shorts. “Hey,” he told Remy, “I hear you could rap.” Unfazed, she rapped a 24-bar verse for a hulking man in his underwear.

I inhale the deepest, cock back and bust rhymes at your speakers

I’m troubled, shoot out the air bubbles in your speakers…

“That might be the one hot rhyme you got,” Pun said afterwards. “Lemme hear something else.” She continued spitting.

Remy Martin, dash, reminisce, slash

Remy, cash like a check in a stash

Me without rhymes is like a flint with no flash

Stripper with no ass, car with no gas…

Pun then asked if she wrote her rhymes. “I thought it was the dumbest question on this earth, like, ‘What do you mean, who writes them?’” Remy remembers. Pun then explained that some women rappers at the time used ghostwriters. “I was like, ‘You’re lying!’ I heard a couple of reference tracks and it really bothered me. I just felt like it was cheating.”

The two verses—which Remy definitely wrote—made her Pun’s prized pupil. She fit right in with the boys. “We were wild and crazy and she was wild and crazy,” says the producer LV. “If you talked crazy to her, she’d talk crazy right back.”

Soon, Pun began work on his sophomore album, Yeeeah Baby, in Sony Music Studios, the fabled red brick building in Hell’s Kitchen where Miracle on 34th Street and Shaft were filmed. Pun camped out in Studio E in the basement for days at a time. When he got bored, he’d prank-call Michael Jackson, who was recording in another room.

Remy Ma was present for most of the Yeeeah Baby sessions. Occasionally, Pun would make her rhyme for visitors, issuing a one-word command: “Rap!” (Like many women in hip-hop before and after her, Remy spent her formative years in the industry having to impress a room full of men.) For the most part, though, Remy, still a novice at this point, listened and learned. Basic song structure, the importance of concepts and a strong chorus became ingrained in her head. “If you’re smart, you soak up all that knowledge and Rem did that every single day. That was her dojo,” LV says. “By the time she got on a record, she knew exactly what to do.”

Pun planned to showcase his new artist on Yeeeah Baby and wanted fans to get that same feeling he had when he sat in his underwear and heard Remy Ma rap for the first time. So he suggested she spit the same rhymes she spit for him that day. The record “Miss Martin,” which features Ma spitting extended verses while was Pun relegated to the hook, made the final tracklist. For the first time, Remy believed she could have a career in rap.

“I’ve worked with Big, Jay, Nas, Big L, Pun, Kool G. Rap, and Jada. I’ve worked with a lot of the greats,” says the producer Buckwild. “Being in the studio with Remy, I had that same feeling.”

What makes Remy one of the most exciting MC’s working today? She is witty and confident and her rhymes are direct, straight to the point. She can rhyme in pocket. Her vocal projection is strong and she has that intangible quality—presence, an aura on the mic. More than anything though, there is a fearlessness to her. She’s never cautious and will not hold her tongue. She won’t shorten her bars or alter something—a simile, metaphor, or dope punch line—because someone might get offended. “A pregnant bitch talk shit, I’ma destroy her fetus,” she once rapped.

She also has a knack for big moments, an ability to recognize when a record is a potential hit, which is why her verses on “Lean Back” and “All the Way Up” are among her best. And she was always ambitious. “Being a rapper was a big deal to Remy. Being the best rapper was a big deal to her,” says Sean C, the producer and record executive who would eventually serve as Remy’s A&R. “It wasn’t about being the best female rapper. She compared herself to male rappers. She wanted to be the best rapper.”

When M.O.P’s Billy Danze thinks about Remy Ma’s ability, the first thing that comes to mind is the “Ante Up” remix. A follow-up to the group’s biggest hit to date, the remix called for something special, and the rugged Brownsville duo had many options. Prodigy and C-Murder donated verses. They were getting something from Jay Z. But Remy forced her way on it alongside Busta Rhymes and M.O.P associate Teflon.

“When I got to the studio one day, there was a blazing-ass verse from Remy Ma on my record,” Danze says. “We weren’t necessarily looking for a female artist to be on the record, but she was able to hold her own in a room full of wolves. There was no way we could pull her off the record.”

Fat Joe took Remy under his wing after the February 2000 death of Big Pun, making her the anchor of his reformed Terror Squad. And the gambit paid off when their record “Lean Back” topped the Billboard Hot 100 for three weeks in the summer of 2004. Afterwards, Steve Rifkind, the founder and chairman of Loud Records and SRC Records, which housed Terror Squad, told Fat Joe he wanted a Remy Ma solo project.

"I’ve worked with Big, Jay, Nas, Big L, Pun, Kool G. Rap, and Jada. Being in the studio with Remy, I had that same feeling."—Buckwild

When Remy Ma began work on the album, she demanded full creative control. After all, the album was titled There’s Something About Remy, and so she managed every aspect of the process from picking beats to brainstorming concepts. She sat with hitmaking producer Scott Storch (Dr. Dre’s “Still D.R.E.,” Beyoncé’s “Baby Boy”) in Miami and came up with the idea for “Conceited.” Then she met Swizz Beatz to concoct “Whuteva.” Because she primarily wrote in the studio, the lyrics were married to the beat and concept of each song. There is little rapping for the sake of rapping throughout the album.

She had ambitions for each record, which led to her butting heads with Fat Joe and Rifkind over the song “Feel So Good.” Joe had lined up Mario, fresh from the no. 1 platinum smash “Let Me Love You” to sing the song’s chorus. But Remy insisted on Ne-Yo, then an unheralded songwriter best known for penning…Mario’s “Let Me Love You.”

Joe and Rifkind wouldn’t budge. “She was adamant about it,” says Rifkind, but he eventually relented. “An artist has to be true to themselves. Nine times out of ten, I’m letting the artist do what they want.” Remy won the battle, but lost the war. Def Jam didn’t allow Ne-Yo to shoot a video for “Feel So Good” because he also appeared on Ghostface Killah’s single “Back Like That.”

“Remy didn’t know how to deal with the politics of the industry,” Sean C says, also citing her notoriety for belittling beat makers. “Producers came in to play her beats and if she didn’t like it, she’d say, ‘Next, that’s trash. That’s wack.’ We had to tell her, ‘You can’t talk to these people like that.’ She would just shit on their beats. Some people didn’t want to work with her.”

“She generally has an idea for what she’s looking for,” Buckwild says of Remy’s beat selection process. “She is honest. The first thing she told me was, ‘Don’t come in here and play no wack shit. I don’t want to hear no wack shit.’ That’s understandable. You want the producer’s best.”

He then tells the story of a certain producer who arrived with 50 beats for Remy. Unimpressed with his work, she began doodling on a piece of paper in front of her. Eventually she held up the drawing. It was the word ‘No’ in big letters and a series of flames. The message was clear: No fire. She told Buckwild afterwards, “He didn’t have anything I liked.”

Remy’s instincts were on point for the most part. Released in February 2006, There’s Something About Remy: Based on a True Story received positive reviews, earning praise for its balance of commercial singles, street bangers, and introspective records. But the album tanked, debuting at No. 33 on the US Billboard 200, selling 35,000 records its first week.

Fingers were pointed afterwards—with good reason. The label pushed “Conceited” to radio while “Whuteva” was still building momentum. The records, of course, cannibalized each other. Remy believed that Universal failed to promote the album or press enough copies. A rift with Fat Joe had also developed. She was eventually banned from the office and dropped from the label.

And then in July 2007, Remy was arrested for shooting her friend Makeda Barnes-Joseph after leaving a Manhattan nightspot; she had accused Barnes-Joseph of stealing reportedly $3000 from her purse. Remy was later found guilty on two charges of assault and sentenced to eight years in prison.

From the moment Remy Ma was released from prison, there was speculation that she would clash with Nicki Minaj. The long-rumoured standoff ended with “Shether,” one of the most brutal diss records in rap history, and its tepid follow-up “Another One.” Nicki Minaj answered on March 9, releasing three new songs including “No Friends,” which took aim at Remy and peaked at No. 14 on the Billboard Hot 100. Fans of each respective artist claimed victory, with Nicki Minaj’s Barbz pointing to “No Frauds” commercial success and Remy’s supporters returning to the superior bars and overall viciousness of “Shether.”

“There are people who will not acknowledge that Nicki lost,” LV says. “This is a hip-hop battle. Remy wasn’t making that shit to get played on the radio. Remy made ‘Shether’ so that me, you, and Nicki would hear it and think, ‘Think again if you want to fuck with me.’ Records like ‘Ether,’ ‘Takeover,’ ‘Back Down’ were not meant to be played on the fucking radio.”

Remy seemed to appreciate the attention afterwards, taunting her adversary on social media and showing up for her appearance on The Wendy Williams Show as if it were Nicki’s funeral, complete with a veil. “I came appropriate for the services,” she joked. Remy took a different tone during her appearance on BuzzFeed’s Another Round podcast. “I don’t regret ‘Shether,’” she said, “but I’m not particularly proud of it.”

The comment to BuzzFeed doesn’t mean Remy laments anything she said on “Shether”—accusing Nicki of using ghostwriters, having butt implants, sleeping with other rappers, sniffing coke, and supporting her brother, an accused child molester. It’s an expression of disappointment that the entire thing happened—especially since, like most rap beef, it could have been avoided with better communication. She must recognize that the battle also fed the perception that there isn’t room in hip hop for more than one woman on the A-list.

“I said what I said and I did what I did. A lot of people’s panties are in a bunch. I think it was a big upset to a few people. But it is what it is."—Remy Ma

After a quiet few weeks, the battle reignited in early June with Nicki Minaj’s verse on 2 Chainz’ “Realize,” in which she accuses Papoose of writing “Shether;” Remy Ma and Papoose’s publicist said they would not comment on the accusation. Remy saved her rebuttal for the Summer Jam stage. Standing side-by-side with Queen Latifah, Lil’ Kim, Cardi B, Young M.A, Monie Love, the Lady of Rage, Rah Digga, and MC Lyte, Remy performed Latifah’s 1993 hit “U.N.I.T.Y.” before launching into “Shether.” Nick Minaj has yet to respond.

When asked earlier this spring if the battle was over, Remy was again reticent. “It depends. It depends,” she tells me. “I feel like I said what I said and I did what I did. A lot of people’s panties are in a bunch. I think it was a big upset to a few people. But it is what it is. I’ve moved on. I don’t talk about it no more.”

She is now working on her solo album Seven Winters and Six Summers, said to be a more intimate project that’ll delve into her experiences in prison. The rich subject matter offers Remy a chance to take risks with her art. Why not make a concept album filled with indelible characters about her time incarcerated—Orange Is the New Black meets Prince Paul’s A Prince Among Thieves with a few potential radio bangers sprinkled throughout? The possibilities are endless: A record about how her marriage evolved during her time away. A record about a certain Christmas or Thanksgiving or birthday that was particularly tough. A record about working towards her bachelor’s degree. A record like “Slippin’” about her insecurities and battles.

“When I used to visit her, there were times when she didn’t really believe,” says Remy’s husband Papoose. “There were times when she didn’t have faith. I would say, ‘Hey people miss you. People love you. People are asking about you.’ It become hopeless because appeal after appeal had failed.”

Doing something different takes guts and ambition, and as record sales dwindle and the definition of a hit turns increasingly nebulous, there’s more room to make weird art that pushes the boundaries of the genre. But it’s up to the artist to create it and turn it into something the public wants to consume.

In the meantime, Remy Ma is pursuing opportunities in television. She was funny and charming during her recent week-long guest hosting stint on the daily talk show The Real. There are also rumors of a Love & Hip Hop spinoff for VH-1 that would focus on her marriage. She doesn’t want to rap forever, not when there are more lucrative gigs in front of the camera.

Remy says she had a plan before she went away to prison, an exit point for when she’d leave the music industry. “The plan was to retire at 30. That was my plan,” she says. “God had other plans.”