I. Can You Just Visualize It?

On September 7, 1996, after exactly 109 seconds, Mike Tyson is declared the World Boxing Association’s heavyweight champion, stripping the belt from Bruce Seldon by technical knockout. If you watch that fight today, you see that Tyson doesn’t crouch, doesn’t bob, doesn’t weave. He stands straight up, backing Seldon into corners, sometimes without throwing punches of his own.

Seventy-two seconds in, Tyson—already the title holder in the World Boxing Council—has knocked down Seldon with a left hook; Seldon gets up, but is knocked down almost immediately by another left. The referee, Richard Steele, steps in and hands Tyson the victory. (A former Marine, Steele was 16-4 as a professional in his own right; he supports a disoriented Seldon on his shoulder.) The fans, who have paid hundreds of dollars to the MGM Grand Las Vegas for tickets, begin to taunt Seldon, chanting about how the fix is in.

Two of the ticket holders that night: Suge Knight and Tupac Shakur. On their way through the lobby, the pair get in a fight of their own, with a Crip named Orlando Anderson; shortly after, at 11:15 p.m., a white Cadillac pulls up beside Suge’s black BMW and opens fire, hitting Pac four times. Six days later, he dies in the hospital.

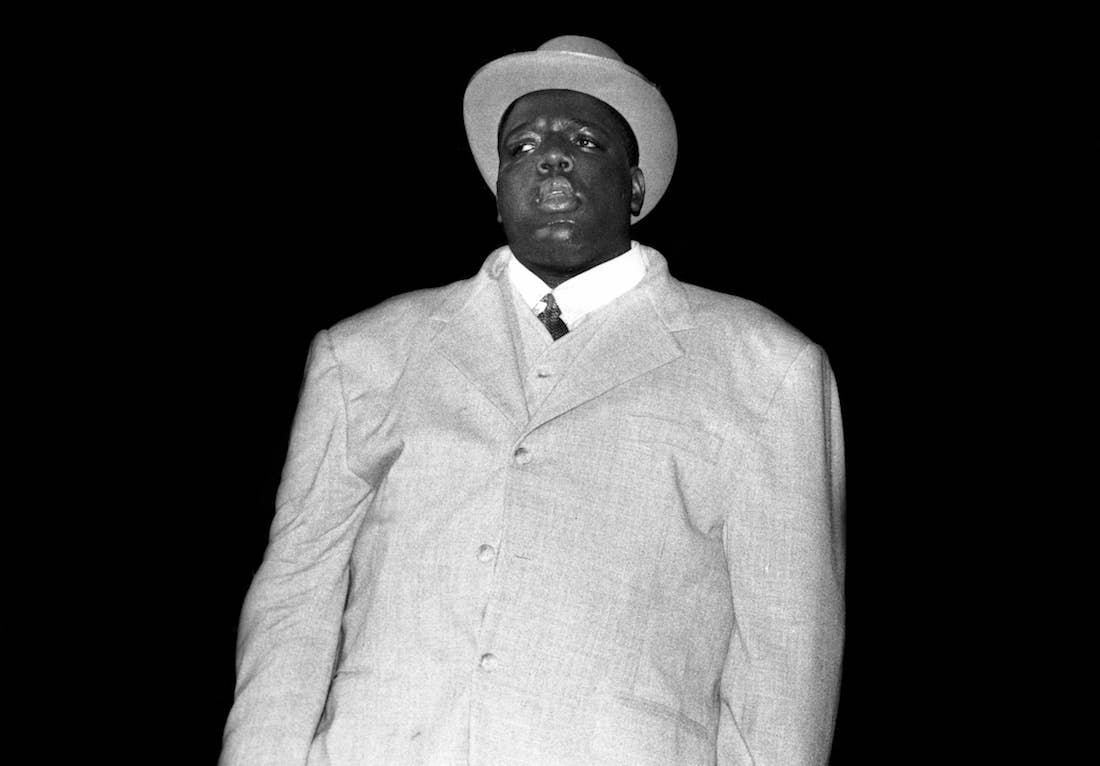

By the fall of 1996, the Notorious B.I.G. was weary. Just a few years earlier, his sessions for Ready to Die had been interrupted by trips to Raleigh, where he ran a modest but profitable drug trade; now he was used to yachts. Big absconded to Trinidad to write and record, supported by Bad Boy’s production team, the Hitmen, and by the cane he used after shattering his left leg in a car crash (“I used to be as strong as Ripple be/’til Lil Cease crippled me”). He was nearing completion on a sophomore album, tentatively called Life After Death… Til Death Do Us Part. It was slated for a Halloween release, but was pushed back due to a litany of issues: sample clearances, marketing rollouts, and so on.

'Life After Death' is the last dispatch from a master. Big perfected nearly every facet of rapping, and did it all before he turned 25. The breadth of his sophomore work is dizzying.

He wouldn’t live to add the finishing touches, but there were certainly some tweaks Big made between Pac’s death and his own. In 2003, Lil Cease told XXL that the album’s penultimate song, the RZA-produced “Long Kiss Goodnight,” originally opened with words about Tupac that were “terrible,” and which never saw the light of day. (In the same article, Puff strenuously denies that the monologue was directed at anyone in particular, but doesn’t offer an alternate explanation for why it was cut.) On “I Love the Dough,” Jay Z says “I’m in the fifteen-hundred seats, watching Tyson.”

The great irony is that, personal animus between Big and Pac aside, Life After Death—as it was ultimately titled—pokes fun at rap’s East-West divide, and at the genre’s posturing more broadly. He quips about looking up to Snoop Dogg and winked at the camera through his radio singles. He raps warmly about his love for Los Angeles—the city he was murdered in, on March 9, 1997, case still unsolved.

Life After Death is the last dispatch from a master. Big perfected nearly every facet of rapping, and did it all before he turned 25. The breadth of his sophomore work is dizzying. It’s massive, but not monolithic; Big indulges his fiercest, funniest, and outright weirdest impulses one by one. The sum total is a double album that can feel too short, real-time legacy building with stakes that would seem silly if we didn’t know how the story ended. In his final months, Christopher Wallace, b. 5/21/72, made the greatest rap record of all time.

II. Puff Won’t Even Know What Happened

In the mid- and late-1980s, hip-hop’s cultural and commercial ground was shifting so rapidly that it could be difficult to pin down. When Kurtis Blow and Whodini gave way to LL and BDP, the question of what it looked like to be a popular hip-hop artist got longer, more complicated. Life After Death was the first album to take as its subject the experience of being a rap star and all that it entails, from feuds to adulation to watching your life get litigated on daytime television.

See the very first verse on the album: Big begins by walking the listener through a murder plot, and right when you start to imagine that this is an alternate timeline where Chris Wallace never left Bed-Stuy, he blurs the line between art and life: “I’m a criminal—/Way before the rap shit/Bust a gat, shit, Puff won’t even know what happened/Ifit’s done smoothly.” So then what about kidnapping daughters on “Hypnotize,” sticking guns in jaws on “Last Day,” doing God-knows-what on “What’s Beef?”

The most obvious bit of professional one-upmanship is on “Kick in the Door,” which is essentially an extended taunt at Nas, Raekwon, and Ghostface, complete with a fourth wall-breaking jab at DJ Premier—who produced the song—for his work with Jeru the Damaja. On “One Day,” from Wrath of the Math, Jeru imagines hip-hop personified, tied up with a gun to its throat, having been kidnapped by Puff, and subsequently by Suge. (The joke is that Big recorded over Premier’s “Kick in the Door” beat despite Puff’s protestations.)

The most pointed barbs Big saved for Nas. On Only Built 4 Cuban Linx…, Ghost and Rae aimed the famous “Shark Niggas (Biters)” skit at Big partially on Nas’ behalf, the charge being that Ready to Die’s cover owed Illmatic for the rapper-as-child theme. Big made no bones about what he thought:

“MCs used to be on cruddy shit

Took home Ready to Die, listened, studied shit

Now they on some money shit, successful out the blue

They lightweight, fra-gil-e

My nine milli make the whites shake

That’s why my money never funny

And you still recouping, stupid.”

Not only was Big knocking Nas for adopting a mafioso personality on It Was Written—he was twisting the knife, apparently alluding to the rumors that Nas borrowed money to buy outfits for the Source Awards.

“Notorious Thugs” finds Big once again hyper-conscious of the expectations that came with Ready to Die’s success. Even the rift with Pac was framed as something outsiders constructed: “so-called beef with you-know-who.” Elsewhere on the album, he was qualifying radio songs (“Fuck You Tonight”) with ski mask songs (“Last Day”). On “Mo Money Mo Problems,” he merged the two, dodging DEA wiretaps with Diana Ross.

Then, of course, there’s “Going Back to Cali.” The intra-city squabbles (Nas rapping about snatching the crown off Biggie’s head) and dissolved friendships (Pac rapping about Faith) were one thing, but Big seemed to find the notion that he should turn on a whole coast ridiculous. In many ways, Life After Death embraces mythmaking, casting Big as a tragic figure too monstrous to be contained by a single disc. But he showed little patience for the paper-thin narratives that he read about in The Source. So you get him flipping LL’s original, dragging groupies to Fatburger, and ending the song, coyly, “Cali: great place to visit!”

III. Tito Smile Every Time He See Our Faces

The band on “Playa Hater” was hauled in from the Blue Angel, the strip club next door and down the stairs from the studio. “Another” sounds raw because Big and Lil Kim were really fighting. That’s Chuck D’s voice on “Ten Crack Commandments”—he sued Premier and Big’s estate after the fact.

Life After Death is ravenously ambitious, but only a few songs are universal in that broad, arena-filling way—the “Juicy” way. Big litters the record with tics, tangents, and inside jokes. (Slotting that “P.S.K.” interlude right before a massive, glossy single is a stroke of genius.) Big was able to run through these experiments—which could have ended up sloppy and disconnected—because at the time, he was essentially peerless as a rapper. The syllables all fell perfectly; he scowled, he rattled off technical passages effortlessly, he lapsed into patois.

Take “Niggas Bleed,” which contains so many of Big’s gifts in microcosm. In the song, he traces a heist from his own internal hemming and hawing (“I kill ‘em all, I’ll be set for life/Frank, pay attention, these motherfuckers is henchmen”) through its conclusion in a sprinkler-soaked hotel hallway. The details are unmistakable: His associate Ron is actually “Arizona Ron,” who drives a black Yukon, prefers the Isley Brothers, then “vanished/Came back speaking Spanish/Lavish habits/Two rings, twenty carats.” As the story unfolds, Big weaves in and out of different cadences, like the spot in the first verse (“They shady? We get shady…”) where he bumps each syllable further back in the measure. On top of that, there’s his biting wit: see the Constanzan “We blazed, they blazed, long story” or the fact that, for all the planning, all the threats, the plot is foiled because the thieves parked by a fire hydrant.

Big was also a wildly idiosyncratic storyteller. Toward the end of “Somebody’s Gotta Die,” he warns his co-conspirator, “See, niggas like you do 10-year bids/Miss the nigga they want, and murder innocent kids,” only to do exactly that himself at the song’s end.

What makes the record feel so three-dimensional is that Big never got jaded...The Big who marveled at his phone bill on “Juicy” didn’t wither up and die. He just bought better cufflinks.

In the way that Life After Death is a rap album about being a rap star, “I Got a Story To Tell” is a storytelling song about telling stories. The verses themselves are remarkable, but switching out of that syntax and re-telling it to his friends at the end of the song was one of Big’s sharpest creative decisions. The Knicks are 691-884 since the ‘96-’97 season.

What makes the record feel so three-dimensional—what makes even the gravest threats tolerable—is that Big never got jaded. “I Love the Dough” is a love letter to fame and fortune; Jay and Biggie hop private jets on a whim, weigh the merits of crab vs. lobster, lose money betting on the Lakers (“gassed off Shaq”) and shrug it all off. The Big who marveled at his phone bill on “Juicy” didn’t wither up and die. He just bought better cufflinks.

IV. Pray and Pray for My Downfall

Of course Big obsessed over death. How couldn’t he? He lived through Reagan and Koch, and as soon as he got financially comfortable, would-be assailants lurked outside of every studio. And so the Dom and steaks and models and Benzes from “The World Is Filled…” are cut off by an anonymous phone call. “My Downfall.” “You wanna see me locked up, shot up?/Moms crouched up, over the casket, screaming ‘Bastard!’/Crying/Know my friends is lying.”

Ready to Die ended with a spiritual reckoning. Big pulled the trigger on himself. On Life After Death, he realized that his death didn’t belong merely to him: there are mourners, murderers, mythmakers to account for. You’re nobody til somebody kills you.

People will point to his album titles, to the last handful of songs, to any number of things to highlight Big’s morbidity. But tucked at the beginning of Life After Death’s second disc is “Miss U,” an elegy for two of his late friends. It’s a song about missing people, sure, but also missing the years you spent together. He raps about selling flour, dodging undercovers, sneaking into movie theaters. How was he supposed to know that the Lexus, LX, four-and-a-half would be suspended in time just the same?

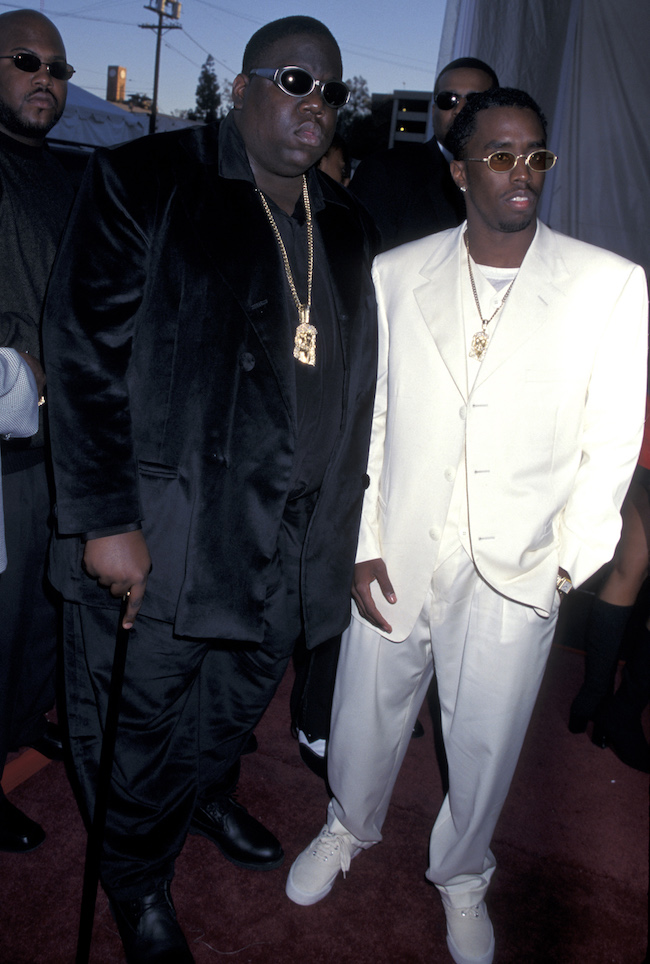

After the funeral, Puff, D-Dot, and Stevie J. sat down to cook up an intro. Can you imagine that session? Of course, the guise is that Puff’s trying to revive Big from the bullet on “Suicidal Thoughts,” not the four from Fairfax and Wilshire. There’s something comforting about the glossy, melodramatic pleading: Big was probably looking down, begging Diddy to take the toothpick out of his mouth.

The line that’s truly chilling comes at the album’s brightest, most shimmering moment, on “Mo Money Mo Problems.” It’s when Puff says, “Nigga never home, gotta call me on the yacht/Ten years from now we’ll still be on top.”

The funeral procession moved on March 16 (“Hypnotize” rattled apartment windows, the police tensed up and pepper-sprayed mourners.) Life After Death came out nine days later; it sold nearly 700,000 copies in its first week. Murals went up, faded, were painted over and retraced. And you’re still recouping. Stupid.