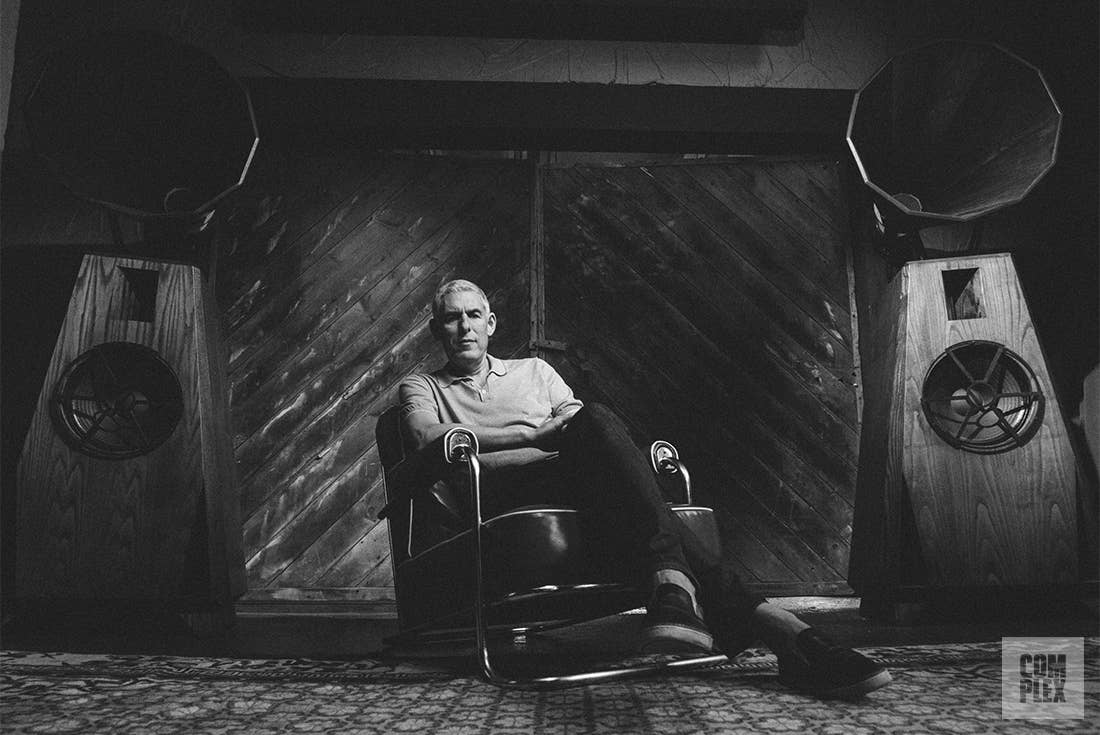

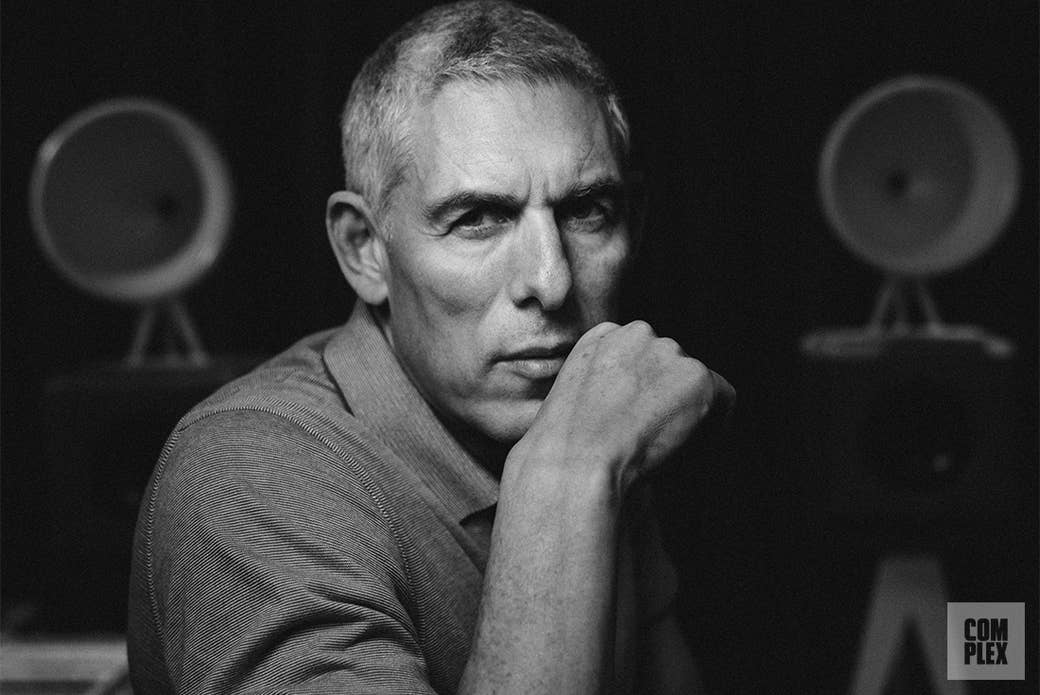

If there were a shadowy Illuminati controlling the world of rap, Lyor Cohen would be its all-seeing eye, the man behind the scenes, pulling the strings of the most powerful players and reaping the benefits. But to meet him in person, you wouldn’t know it. On a recent summer day, Cohen enters a Dumbo loft apartment in good spirits, sporting a blue polo shirt, blue jeans, and sandals, unassuming and “happy to be alive,” in the words of his publicist, after suffering a pulmonary embolism in April. He’s been documenting the recovery on Snapchat, featuring videos with Khalid, his doctor, and DJ Khaled, his friend.

Born in New York and raised in Los Angeles, Cohen has a résumé that reads like a textbook on hip-hop history. He’s known as the prime mover behind Run-DMC’s seminal Adidas endorsement, the man who convinced Def Jam to split off from Sony Music Entertainment and develop Island Def Jam, and, thanks to a famously fierce temperament, the no-bullshit businessman who will burn one bridge while erecting three more.

His impressive client list is a power circle filled with monolithic old-school figures and influential newcomers: He’s worked with Jay Z, Run-DMC, DMX, Kanye West, Young Thug, and Fetty Wap, to name but a few. In 2012, Cohen left his role as the chairman and executive chief at Warner Music Group to found 300 Entertainment, a company Forbes refers to as “a record label for the 21st century...capable of launching self-starting artists to the next level without the burdensome bureaucracy—and cost structure—of a major record company.” The idea: to create a boutique “independent” music collective, a gang of enduring content creators.

His new venture is still in its infancy, but Cohen’s roster—which features Thug, Fetty, and Migos, among others—suggests that his influence still runs deep. To learn his secrets to the industry, and what it feels like to pull those strings, Complex sat down with Cohen to pick the puppet master’s brain on his ventures in hip-hop, both past and present.

It’s been four years since you founded 300. What’s the attitude of the label today?

I always say, “We’re a 218, even though the name of our company is 300.” So our aspiration is to become 300. But in terms of communication, transparency, rewarding risk, we’re like a 218.

I want people to put themselves at risk. If we’re having a meeting and you’re not saying anything, then you’re sandbagging and you’re pimping all of my effort. If you don’t have any ideas, that means you’re not willing to put yourself at risk. It takes a thousand dumb ideas to come up with one great one.

How do you enforce that?

There’s an expression called, “Being a hater.” A hater is someone who wants to be right more than they’re wrong. What I’m trying to get at the company is the opposite of a hater. I’m looking for lovers, who are willing to suffer through the nine losses to get to those one or two artists who hopefully help all of us enjoy our lives a little bit more because they exist. I try to find people who aren’t haters, who want to go through the anxiety and difficulty of finding that glorious act. It means a lot of heartache on the way.

Young Thug has certainly been one of those artists for you, but he’s been notoriously mysterious. On CNBC’s Follow the Leader, however, you advised him to devote more time to his public persona. Can mystery be a good thing?

I think mystery is a very good thing, and I don’t believe in shameless promotion or access.

I do believe, like a beautiful flower, and how it goes from a tight bud and evolves into a flower itself, that there are inflection moments of revealing different parts of the flower. That also applies to careers. Mystery is underutilized and not respected as much as it should be, but it’s more about sequencing. Create a mystery because then the reliance is on the music. The reveal is then the music, not the personality. But there is a certain point at which that hand is overplayed, and it’s time to reveal a little bit more.

"I don’t know what the definition of a label should be. I know what it once was, but it’s no longer."

Does 300 help tailor personal narratives for its artists?

I don’t believe that’s our role. Our role is to help develop truthfulness and to be a good sounding board. We’re not concocters. That’s never been how I see record companies. I see labels as safe havens for creative people to push the boundaries. Concocting and scheming messages is not really in our purview.

Well, for example, I’m thinking of how Fetty Wap, when he came out of nowhere with “Trap Queen,” was presented as this humble, grateful person, which makes him more likable.

The thing you have to understand is that a lot of young people go from radical obscurity to celebrity, and that’s traumatic in its own right. Helping them through that celebrity is much more in our purview. Once they get their bearings and understand, “Wow. I went through this inflection of going from obscurity to celebrity. I’m not sure how I like it. How am I able to navigate?” If you went from “off-the-beaten-path journalist working at Complex” to Philip Roth, you would go through your own set of trauma and insecurities.

You’ve spoken a lot about artists’ incubation periods, the time it takes for them to get to the right place creatively and professionally. Do you think the Internet has a negative influence on that incubation period?

Everybody I know who has fought the Internet has lost. This is a riptide you could have working for you or against you. ever fight the riptide. You’ll die. Instead, go with the riptide. It stops at a certain point, and then you’re on safe ground. Sometimes the Internet extends or retards the incubation period, and sometimes it short-circuits and makes it much quicker. If you have a really good team, and you can overcommunicate and talk about things, you can recognize what’s happening, and act accordingly.

Do you have any advice for entrepreneurs trying to court artists to their label?

It’s being in the mix. It’s not mailing it in. It’s presence. In the Bible, God is a central figure, but he doesn’t show up for many, many chapters. The first thing he says is, “I am here.” Physical presence of self is powerful, especially in the era of the Internet. One of the things the record business has lost is that presence of self. The relationship—he consistent and ever-present relationship.

What do you think when artists go off on their own and abandon the music industry?

I applaud them. It makes a whole lot of sense. I think it’s unbelievable. I don’t know what the definition of a label should be. I know what it once was, but it’s no longer. The artists don’t need them in that capacity anymore.

What advantages does 300 offer to someone like Chance the Rapper, who is already successful?

300 offers a more boutique experience. There’s no taking a ticket and waiting in line. It offers consistent presence of the principles. It offers capital. It offers a sounding board of professionals who have done this for quite some time. It offers unique opportunities and not cookie-cutter deals that aren’t imaginative.

"I don’t believe in exclusives. I think it’s damaging to our industry. I believe in ubiquity."

Will 300 ever follow the lead of Kanye West, Frank Ocean, and others and do exclusive releases to, for example, to TIDAL or Apple Music?

I don’t believe in exclusives. I think it’s damaging to our industry. I believe in ubiquity. I don’t think streaming services should win or get a leg up because they have an exclusive. They should get a leg up because they’re the best consumer experience. It fractures the consumer experience if you sign up for Spotify or Apple or TIDAL or Rhapsody thinking that you’re getting most of the world’s music for $10. When one has an exclusive or another has an exclusive, it’s interrupting the process of paid subscription. And I don’t like it.

In 2014, Dame Dash accused you of “continuously making money off our culture,” and “not using any of your money to help our culture.” What do you say to that?

As it relates to Damon, I don’t see him or hear him. I wish him the very best. I hope he finds his way, and finds a way to contribute and feed his family. As far as community work, that’s private for me, but it’s also public. Everyone knows I’m a proud board member for over a decade of Boys & Girls Harbor. We help thousands of kids in the inner city, primarily in Harlem, through the arts and school. In after-school programs, the working poor tend to get screwed the most, because there’s a net and an apparatus for the most severely poor people. But when someone has a job,their kids get out of school, and they live in a rough neighborhood, but the parent can’t pick the kid up from school, there’s not an apparatus for that. We provide a net and safe haven for those kids to study, play sports, perform in the arts. Everyday I wake up trying to give more than I receive.

What advice would you give to a kid who wants to make it in music?

Be certain you love it, because that could help fuel you to survive the very low moments. Very few people actually can feed their families in the creative arts business. If you really love it, you will tolerate the suffering that you need to go through.